Food or Fertilizer? Edison Students Explore the Use of Bugs in Global STEM Challenges Program Ahead of Earth Day

Earth Day comes just once a year, but the Global STEM Challenges Program at Thomas A. Edison High School has students tackling major environmental issues year-round.

The three-year program, in which ninth-graders focus on food access and agricultural issues, tenth-graders target clean water and eleventh-graders contemplate sustainable energy, bears many similarities to the efforts of Earth Day celebrations.

“Our goal is to teach students to break the mold in thinking about critical issues for our society and our planet,” lead Global STEM Challenges Program teacher Chris Kniesly, says. “In a traditional classroom, things are very prescribed, you teach a set of circumstances and students are tested on their understanding. In this program, we want students to upend circumstances so they can become changemakers in their future careers.”

Global STEM Challenge Program students take math, science and engineering classes with an emphasis on developing skills that universities and employers want, like collaboration and critical thinking. They are tasked with problem-solving in teams of their peers, researching current solutions to vexing global matters and then coming up with their own plans to tackle them.

High school freshmen in the program are eyeing everything from new approaches to agricultural options in urban apartment buildings to the protein-rich possibilities of insects as food.

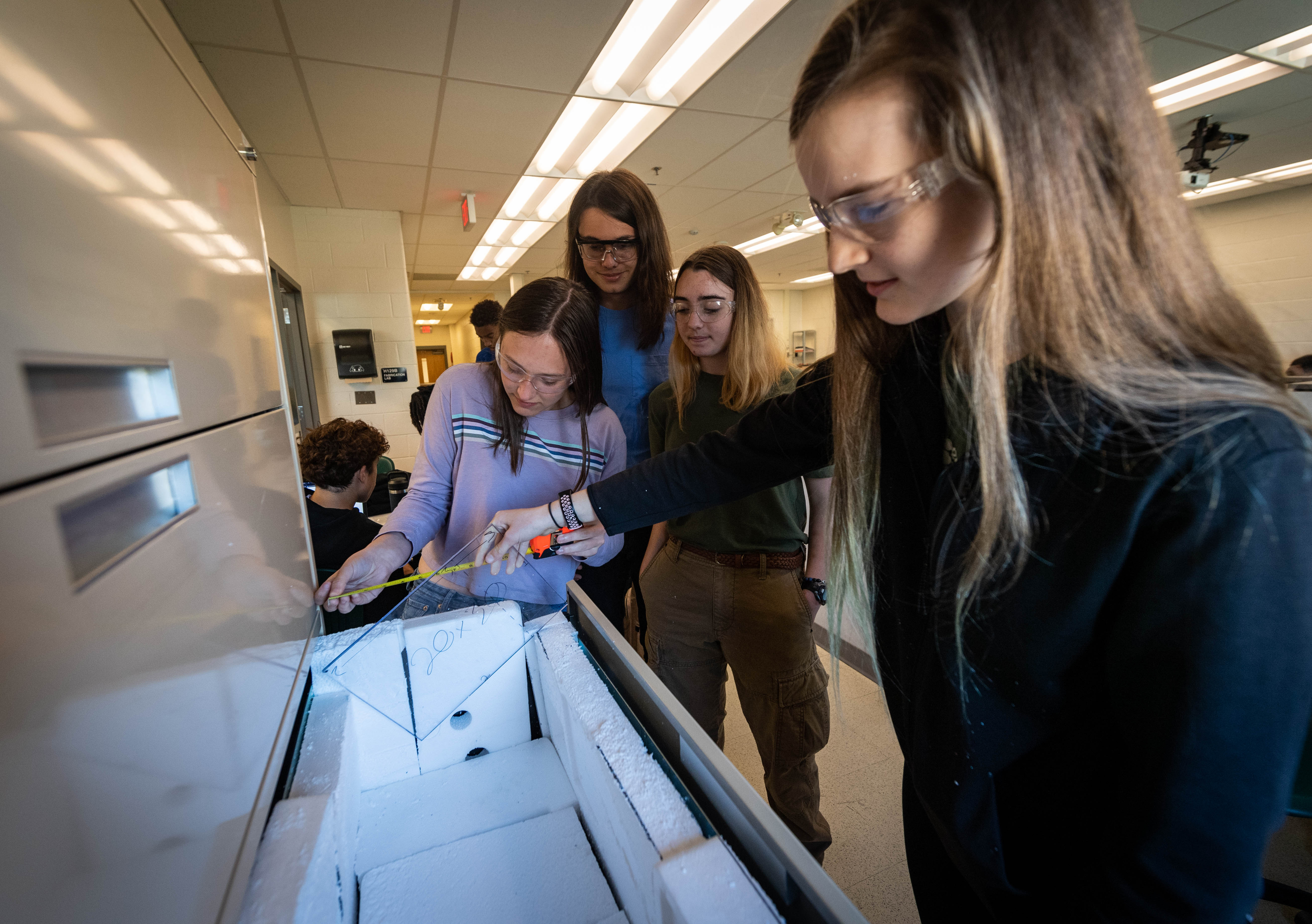

Caitlin Brickley, Zachary Miller, Layla Cross and Arcadia Perszyk have turned an unused file cabinet in a Fairfax County Public Schools storage warehouse into a bug incubator.

The approach incorporates tenets of the Global STEM Challenges Program by upcycling existing material – the unused file cabinet, which also takes up less floor space since it is a vertical container. Students have transformed the file cabinet into a home for black soldier flies,

and plan to use their larvae as a more environmentally friendly food source.

The bugs “sort of automatically harvest themselves” by climbing to a higher stage of the filing cabinet, and then dropping into a bin right when they are at the optimal stage of development to be turned into food, Zachary says.

Students hope to target a younger audience, between ages 5 and 25, who may still be open to the idea of eating bug larvae.

“If you know where to look, there are plenty of recipes to be had using black soldier fly larvae; we’ll be starting with cookies,” Layla says. They plan to recruit a group of school-age students to serve as taste-testers for the bug cookies, to see if they can tell the difference between regular cookies and the ones made with the larvae.

“Current methods of food production – cows, sheep and pigs – take up a lot of resources,” Arcadia says. “This has the potential to be a lot cheaper, and it’s also quite high in protein.”

In the same classroom, Nathan Hodge, Aydin Guleyupoglu, Joaquin Tamanaha and Marcus Owusu are also evaluating the dietary and agricultural contributions that insects could make.

“Our overall goal here was to create a more sustainable source of protein, we had a teacher bring in a bag of cricket-based cheese puffs, they were pretty good actually,” Joaquin says.

Nathan says the group is building a container for mealworms, gathering their “frass” or waste product, which will drop through a mesh lining on the bottom of the crate into a collection unit. The waste is a “really good source of fertilizer,” he says. Mealworms happily eat plastic, PVC and styrofoam, thereby reducing the waste associated with those materials as well, he says.

Two other cohorts are focused on finding ways for big city residents to be able to grow their own food, boosting access to locally grown produce and reducing pollution from transporting agricultural products at the same time.

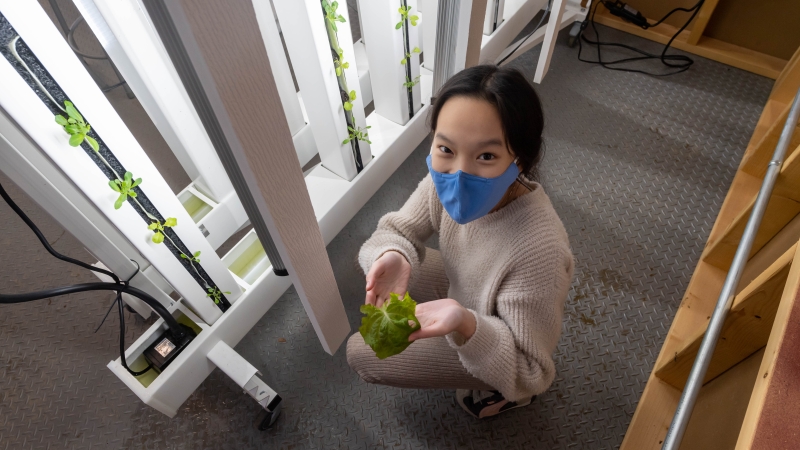

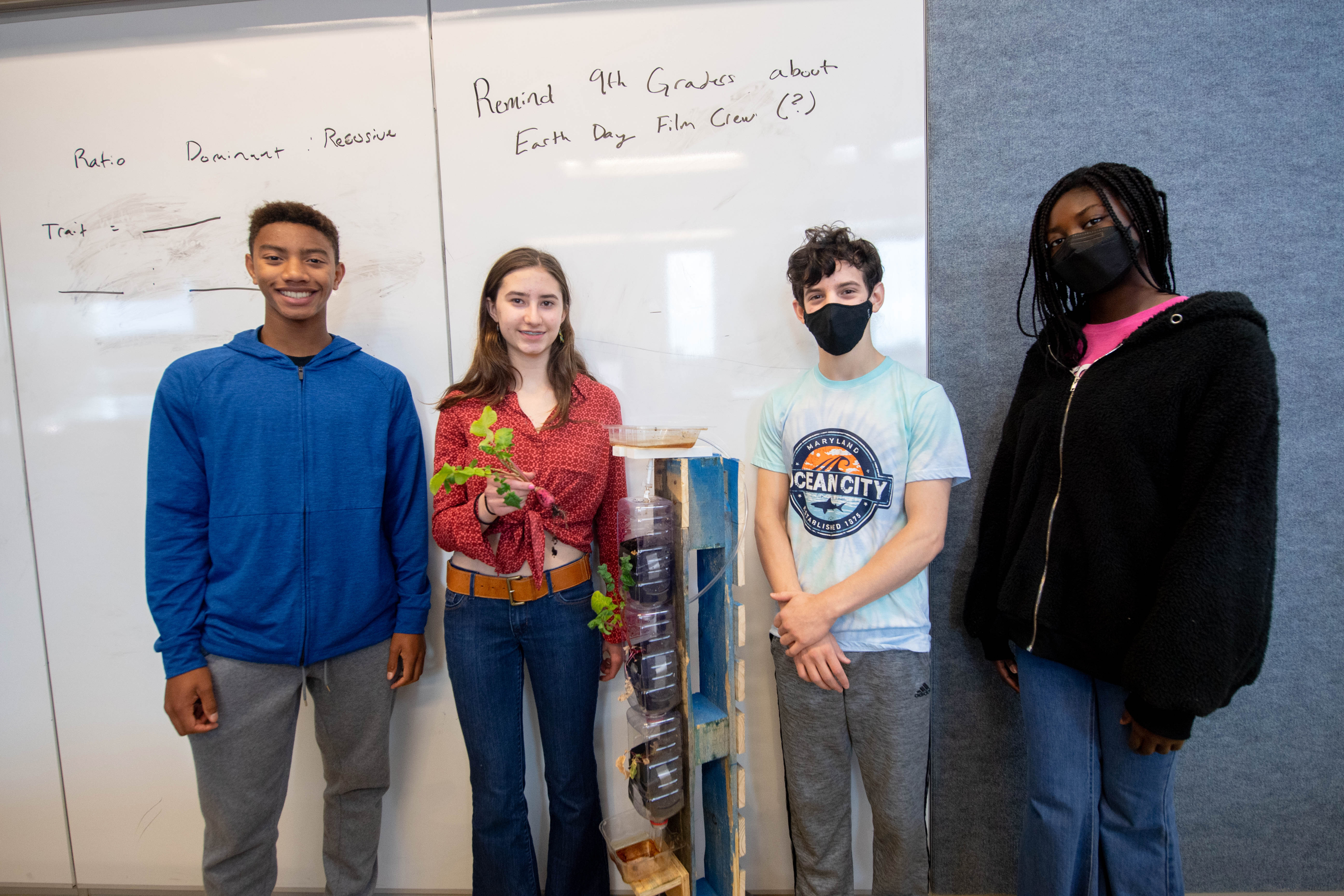

A vertical garden created by one group is intended to conserve both space and water, team members Zoey Hewton, Laurel Heinzen, Jalani Marshall and Aydin Guleyupolgu say.

The group started by finding discarded items at their school – incorporating wood from pallets used to deliver food and old milk cartons – to create their vertical farming structure to grow radishes and recirculate water between the various plants.

“There’s so many different ways to use things you think may wind up in the trash,” Laurel says. “We reworked everything in new ways to become more space efficient.”

Jalani added: “Our hope is this type of gardening makes farming more accessible in apartments and smaller spaces.”

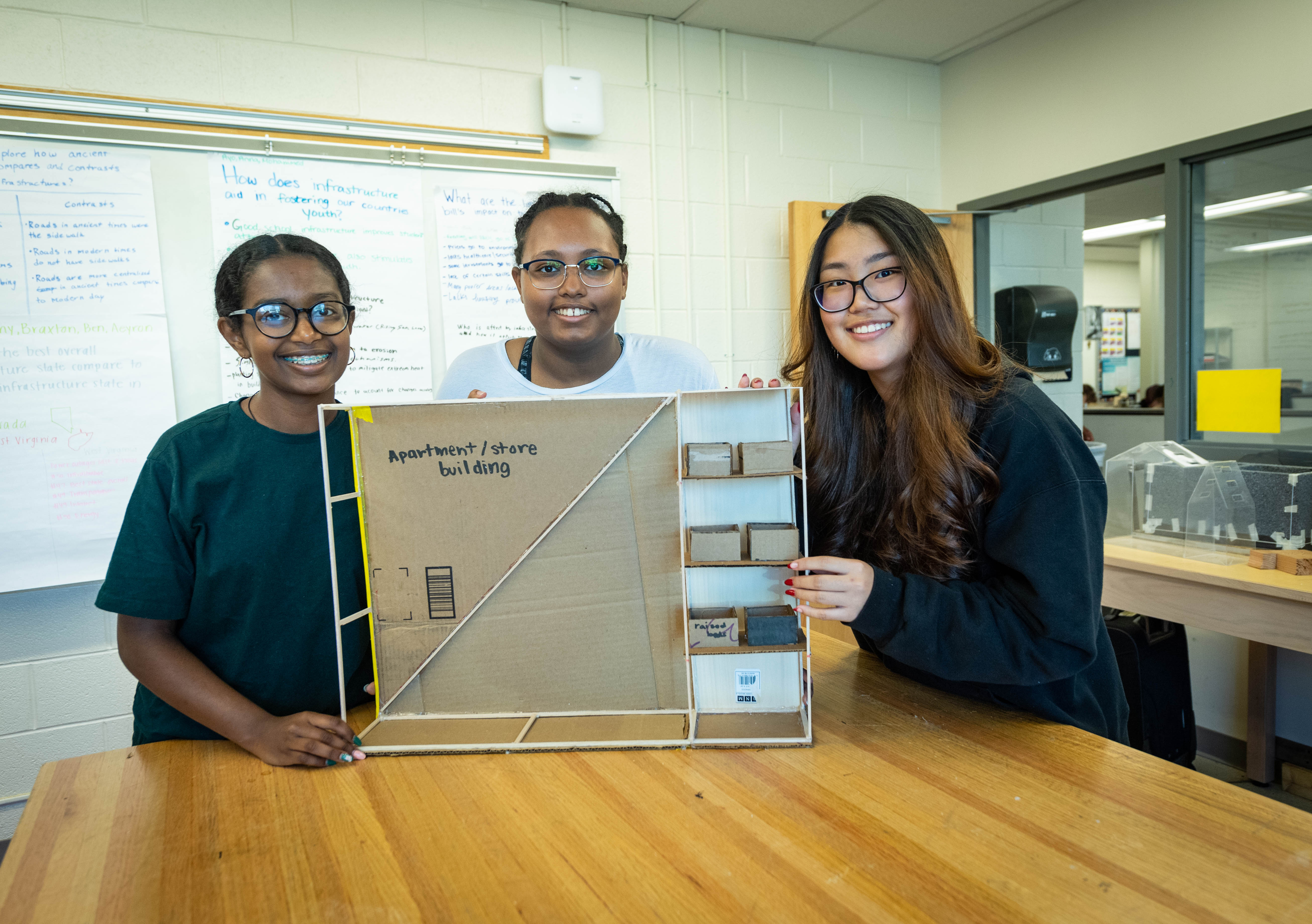

Fellow freshman Dinah Teshome, Liyat Sisay and Emma Srithongkum constructed farming architecture that could serve as an extension to apartment buildings, including several levels of plant beds in which water from each bed can drip down to the next to conserve resources.

“Food grown can be used by families in the building, you don’t have to worry about produce rotting in transit so we’re reducing waste, and if you’re not moving large quantities of produce in trucks, you’re also not contributing to air pollution transmitted by vehicles,” Dinah says.

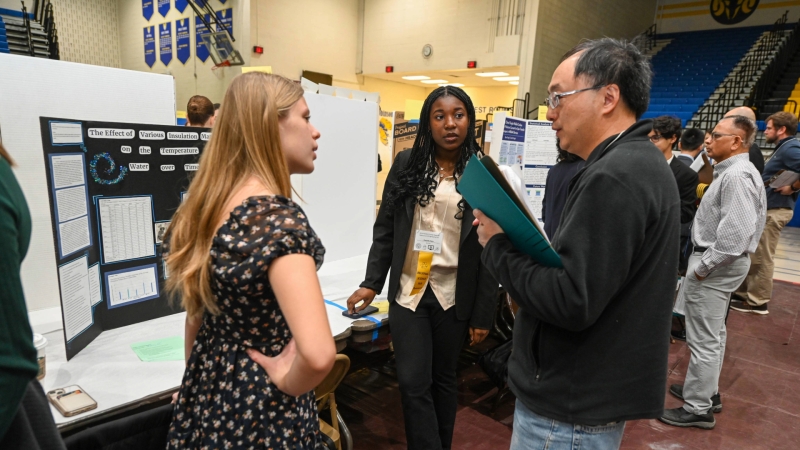

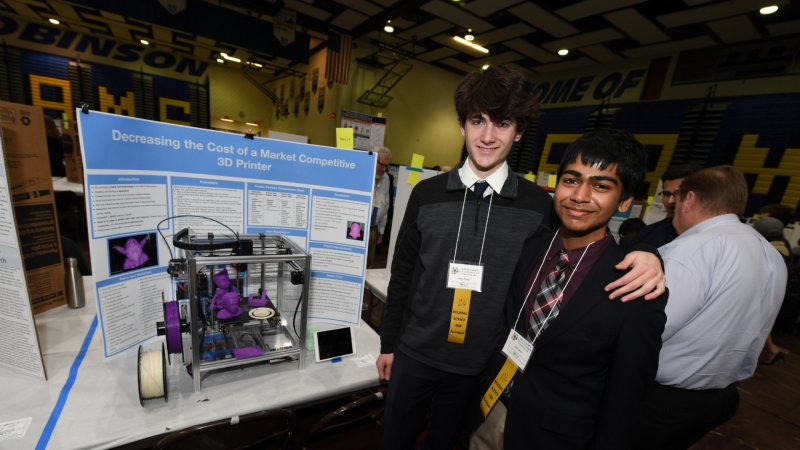

After projects are complete, Global STEM Challenge program participants typically are asked to present their solutions to their classmates, teachers and occasionally community members or industry representatives to give the students experience public speaking and exposure to the business world.

Integrated Engineering/Tech Ed teacher Desanka Elwell says she knows the students are picking up ways to help the planet, and also their future selves.

“My hope is our students learn how to problem solve and also how to work with different teams,” Elwell says. “The cooperative work of teams is integral to this program because every one of these students will need to know how to work with other people in their future careers. Some you will get along with, some you won’t, and that is life so I am glad to give them a chance to work on those skills now.”

Edison freshman Aydin Guleyupoglu says the real-world applications of the Global STEM Challenges program are what drew him to the course.

“I signed up because I thought it would be cool to try a new way of school, instead of just textbooks and math equations, we apply knowledge to real life problems and scenarios,” Aydin says. “I want to continue doing this type of classwork. Instead of memorizing things, our teachers give us the basis of a topic, and then push us to go out, research the issue and we take it from there.”

Read more about the Global STEM Challenges program.

Learn how to apply to the Global STEM Challenges program.

Read about Luther Jackson Middle School’s foray into vertical farming.