Point of View

Learning the role of view point and understanding that each person has a unique point of view is one of the most important thinking skills that a child can acquire.

Everyone has a viewpoint!! Learning the role of view point and understanding that each person has a unique point of view is one of the most important thinking skills that a child can acquire. It is not only important for children to become comfortable sharing their own view point, they must also be willing to listen to and learn from the view points of others. They will also learn that their own view point is stronger when there is evidence to support their thinking.

This thinking skill takes practice; however, over time, children will learn that knowledge and ideas can be examined from many different points of view and by considering different viewpoints, they will gain a deeper understanding of situations, issues, and beliefs. Learning to examine various viewpoints will increase their willingness to consider the ideas of others and help them understand that their own point of view is subject to change. Gradually, with practice, they will be able to listen to and learn from others, think critically about their own ideas, and identify areas of agreement and disagreement.

Parents can help their children recognize and appreciate different viewpoints through conversations that encourage a discussion of open-ended questions e.g., what makes a good friend? What is your favorite sport and why? Movies and books yield additional opportunities to discuss different view points on whether each person liked or disliked the movie or book and why? If the movie is based on a book, which one did you enjoy more and why? How were they alike? How were they different? When children are encouraged to participate in conversations where they have an opportunity to share their view point, they become more confident and comfortable with sharing their thinking and are more open to considering the ideas and opinions of others.

There are many children’s books available that provide children with an opportunity to consider a different viewpoint. For example, The True Story of the Three Little Pigs is a traditional story told from a different point of view, in this case the wolf’s. After reading this story, parents can discuss how the wolf’s viewpoint differed from that of the pigs’. They can also discuss what they thought about the wolf’s view point and whether or not he had evidence to support his claims. Children can then be asked to consider another story from a different viewpoint. For example, in the story of The Three Bears, how did the bears view a stranger coming into their home? How did Goldilocks view the bears? How did their viewpoints impact the story?

Once they are comfortable with the notion of viewpoint, children can learn to practice using evidence to support their thinking. If they like a certain book or story, they can be asked to provide examples from the story to support their view point. This gives them an opportunity to experience firsthand the effectiveness of using evidence to support and illustrate their ideas.

They learn that it is not enough to just say, “This is my favorite book!” but to add details that will encourage another to read the story as well. If someone disagrees with them, it becomes more than just who is right or wrong, but a situation in which each person has a different view point and they should listen to and understand the other’s view point as they form their own opinion.

Another strategy for sharing varying view points and ideas is the Socratic dialogue. Named for the ancient Greek philosopher who believed that all knowledge is living and interactive, it is a method that teaches through questioning. Socrates believed that actively questioning another’s ideas helps that person discover what he or she believes and is the basis for his or her beliefs as well.

The Socratic dialogue provides a safe and engaging forum for students, parents, siblings, and peers to consider multiple viewpoints as they listen to and learn from each other. The questions are a catalyst for lively discussions that lead to a deeper understanding of thoughts and ideas.

To begin a seminar discussion, the leader (adult or child) poses an open-ended question e.g., what is potential? The first question may lead to other questions, e.g. does everyone have the same potential? What must you do to make sure that your potential is developed? Participants share different viewpoints, support their opinions with clear reasoning and evidence, consider alternative views, and identify areas of agreement and disagreement. Through this dynamic discussion, children will increase their understanding and expand their thinking in new and meaningful ways. Christopher Phillips, often known as the Johnny Appleseed of Socratic dialogue, has several books that provide wonderful questions to stimulate Socratic dialogue. These include the The Philosophers Club and Ceci Ann’s Day of Why.

Family seminars may start out as open-ended questions; however, they may also be in response to a poem, news article, artwork, movie, or other piece of interest that would lead to a good discussion. After reading My Great Aunt Arizona, by Gloria Houston, a story about children who attended a one-room schoolhouse in the 1800’s, children in one family discussed, what were the advantages and disadvantages of one-room schools? Another family read the poem, A Road Less Travelled by Robert Frost. After sharing the poem, they discussed the importance of making thoughtful decisions and wondered whether you can ever really know if you made the right decision as you go through life?

The flow of ideas that the seminar fosters challenges participants to question and defend their own thinking as they listen to others. It also provides children with practice in expressing and sharing their own thinking and ideas. Family discussions are raised to a new level when children and parents are engaged in this strategy and the thinking skills as well as confidence that a child learns through Socratic dialogue at home will carry over into school and life.

Finally, as a link to the next strategy, Decisions and Outcomes, students can also be asked to express their viewpoints on a decision that was made and its various outcomes. Often, their view point will change over time once they experience firsthand and reflect on the outcome of a decision. They will also gain a deeper understanding of how decisions and outcomes impact viewpoints and what it means to learn from experience. As students become actively engaged in these thinking processes, they learn to test and reflect on new ideas in an environment that nurtures critical thinking and life-long learning.

Related Pages

Research - The Road to Action

Teaching children how to research is a critical skill that can start early and will serve them for a lifetime. In today’s world, where there is so much information readily available at our finger tips, it is never too early to begin to teach children how to search with a “critical eye”.

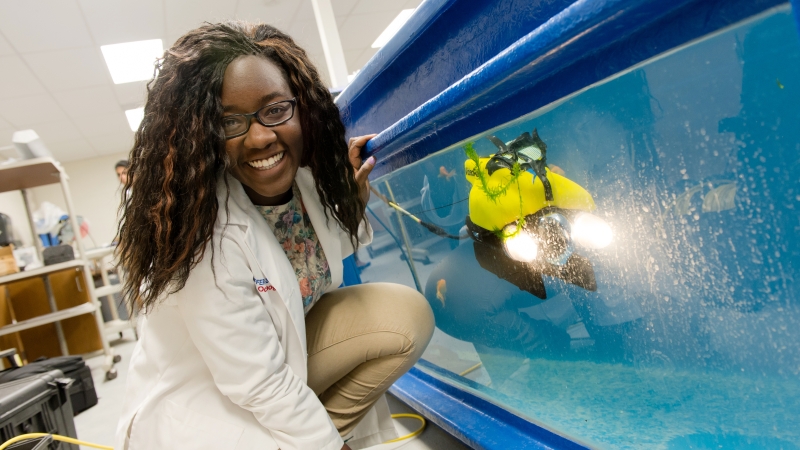

Creative Problem Solvers

The significant problems we have cannot be solved at the same level of thinking with which we created them.

Creative Brainstorming with SCAMPER

Brainstorming encourages children to think of new ideas, combine existing ideas in new ways, and generate original and often unusual ideas.

The Art of Persuasion

Persuasion is used quite broadly in today’s society.

Colorful Thinking

What color is your thinking? Six Thinking Hats, a book by Edward DeBono, provides a colorful structure to guide children as they discuss a topic or issue from six different perspectives.

Analogies: Creative Connections!

A facility for working with analogies gives children a structure for generating creative ideas, seeing complex relationships, and making unusual comparisons.

Decisions and Outcomes

“You can’t judge a book by its cover” is an age-old adage that lies at the heart of this decision-making strategy.